Twentieth century watchmaking is shaken by a vast movement, which profoundly transforms the face of the global industry: first with the development of wristwatches, which proudly appear at the wrists, then with the appearance of the quartz watch and the mass production of electronic timepieces, at the expense of the traditional mechanical industry specific to Switzerland (this will be called the “quartz crisis”). It will be necessary to wait until the very end of the millennium so that the mechanical watch, in particular by means of the chronograph, gives back its colors to the Swiss watchmaking. Discover the history of watchmaking during this period.

The wristwatch, birth certificate of twentieth century watchmaking

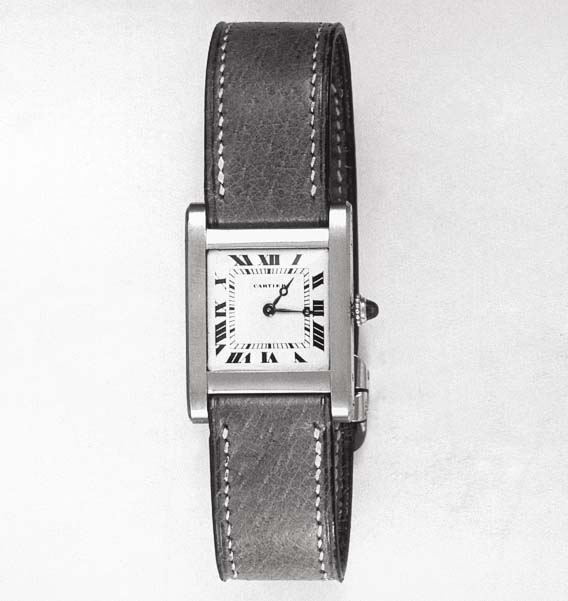

If it were necessary to determine the precise moment of the birth of twentieth century watchmaking, it would certainly be at the moment of the appearance of the modern wristwatch. It is to answer a specific request of his aviator friend, Alberto Santos-Dumont, that the watchmaker Louis Cartier (associated with Hans Wilsdorf) designs a watch intended to be worn only on the wrist, so that the pilot can watch the time without having to pull his chronograph from his pocket.

This happened in 1904, nearly a century after Abraham-Louis Breguet made the first bracelet with a timepiece offered to the Queen of Naples (and nearly two and a half centuries after Blaise Pascal had the idea of tying your pocket watch around your wrist with a string). But this time, when the Santos model is marketed from 1911, the world of watchmaking is ready to replace the famous pocket watch, privileged fashion accessory of the male until the end of the First World War.

However, the first models are echoed mainly by women, and less as a precise instrument for measuring time than as an accessory. In men, it will be necessary to wait for the process of virilization of the wristwatch by the military (and in particular the pilots of planes) so that the object ceases to be regarded as wacky and effeminate.

The need for precision and the revolution of the quartz clock

The history of watchmaking is also that of a quest for more and more precise precision. It is in this light that, following the discoveries of the Curie couple on the piezoelectric effect of quartz, the Americans Warren Morrison and J.W. Horton develop, in 1928, the first quartz clock; because of the properties of this stone, its clock is infinitely more reliable than mechanical systems – with an accuracy of the order of a thousandth of a second per day.

With the gradual miniaturization of quartz movements, the Japanese industry manages to introduce a first quartz watch model in 1969 – a watch that uses a quartz oscillator set in motion by electrical stimulation. It is due to the company Seiko, already known for having produced the first pocket chronograph of Japan.

Research in this field continues with the development of atomic clocks, from 1947. These clocks rely on the immutability of the electromagnetic radiation of the electron to ensure the accuracy of the oscillating signal; these instruments can thus impose time scales of reference on the whole planet (the “international atomic time”).

Another novelty – or rather a development – stems directly from this quest for precision specific to twentieth century watchmaking: the rise of the chronograph. The watch equipped with a complication to measure the duration of an event with the help of an additional needle knows its hour of glory from the first part of the century. Omega is the iconic brand since that time, with the manufacture of chronographs used for sports timing during the Olympic Games; but we can also mention Longines and Heuer, who dominate the scene before the Second World War. (Note that the difference between the chronograph and the chronometer is a matter of precision: a chronometer must necessarily have obtained a certificate from the Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Office.)

Switzerland, the quartz crisis and the birth of Swatch

If the mechanization of watchmaking came from the United States since the middle of the nineteenth century did not put at the carpet the Swiss industry, which has been able to adapt to the new market, the twentieth century causes him much concern. The earthquake of the Great American Depression causes turmoil on the Old Continent; in Switzerland, the watch industry is still dominated by family businesses, which are too small and hit hard by the economic crisis. Parts manufacturers, in particular, soon find themselves in great danger, so much so that the Confederation must associate with the banks to found a holding company intended to bring together these craftsmen, without whom the industry can not survive (they are the ones who manufacture pendulums, spirals and other clockwork stones).

But the real storm comes later, in the 70s. The appearance of the quartz watch has allowed Japanese industries to flood the market with electronic timepieces offered at unbeatable prices. Americans are following suit, placing palatability for quantity over the need for quality. The so-called “quartz crisis” is shaking the Swiss watchmaking empire with its expensive, high-end artisanal design that it threatens to collapse. In 5 years, the market share of Swiss automakers goes from 50% to … 5%!

Fortunately, watchmaking of the twentieth century sees its own geniuses appear; these are no longer major inventors as were Breguet or Jaquet-Droz, but rather brilliant businessmen, able to read the thoughts of the market. This is the case of Nicolas Hayek, a Swiss naturalized Lebanese who, in the early 80s, is asked to analyze the causes of the sinking. The creation of the Swatch stems from this particularly harsh audit: with this timepiece combining quality, speed of manufacture and low labor costs, Hayek literally saves the domestic industry and allows Switzerland to to extract with happiness from the quartz crisis.

After quartz: back to mechanics

Despite the predominance of Japanese quartz watches, whose market for the first time exceeded in 1982 that of mechanical watches, the Swiss industry emerged from the crisis thanks to Nicolas Hayek and his millions of Swatch sold worldwide.

Like all the mechanical complications, the chronographs suffer from this evolution: with the digital watches of the 80s which gladly take on a chronograph function for reduced prices, the buyers abandon the more qualitative models, more artisanal, but also much more expensive .

In the 2000s, however, there was a strong comeback of mechanics in the Swiss watch industry, which is once again positioning itself successfully on the luxury sector. The chronograph embodies this renewal: the sales figures increase from 1 million pieces in 1990, to 4.2 million in 2000 and to 5.3 million in 2010.

After the quartz crisis and the battle of the quartz watch, the Swiss manufacturers are refocusing on craftsmanship. They manage to intelligently transform the timepiece into a luxury, tradition and fashion product at the same time, highlighting Swiss know-how as a symbol of prestige inaccessible to the greatest number. Of course, the Swiss watch industry no longer dominates in terms of market share; but it remains first in terms of market value.

Français

Français