Did you know? It was France that saw the birth of the modern watchmaking industry, as it developed from the 15th century onwards and continues to spread its expertise worldwide, particularly from Swiss workshops and Japanese laboratories. At certain points in its history, French watchmaking was at the forefront of watch design and manufacturing, with Parisian workshops being vibrant centers of national excellence. Join us as we delve into a history where the mechanics didn’t always run smoothly!

The Prehistory of French Watchmaking

What if the first true watchmaker had been French? Around 1292, the name of the man considered the very first representative of his profession appears in history: Jehan l’Aulogier. At the same time, the famous Roman de la Rose refers to a mechanical clock for the first time in a literary work. This was undoubtedly the moment when the millennia-old quest for time measurement shifted into the realm of precision, abandoning instruments that, until then, drew time from the sun’s course or through the flow of water.

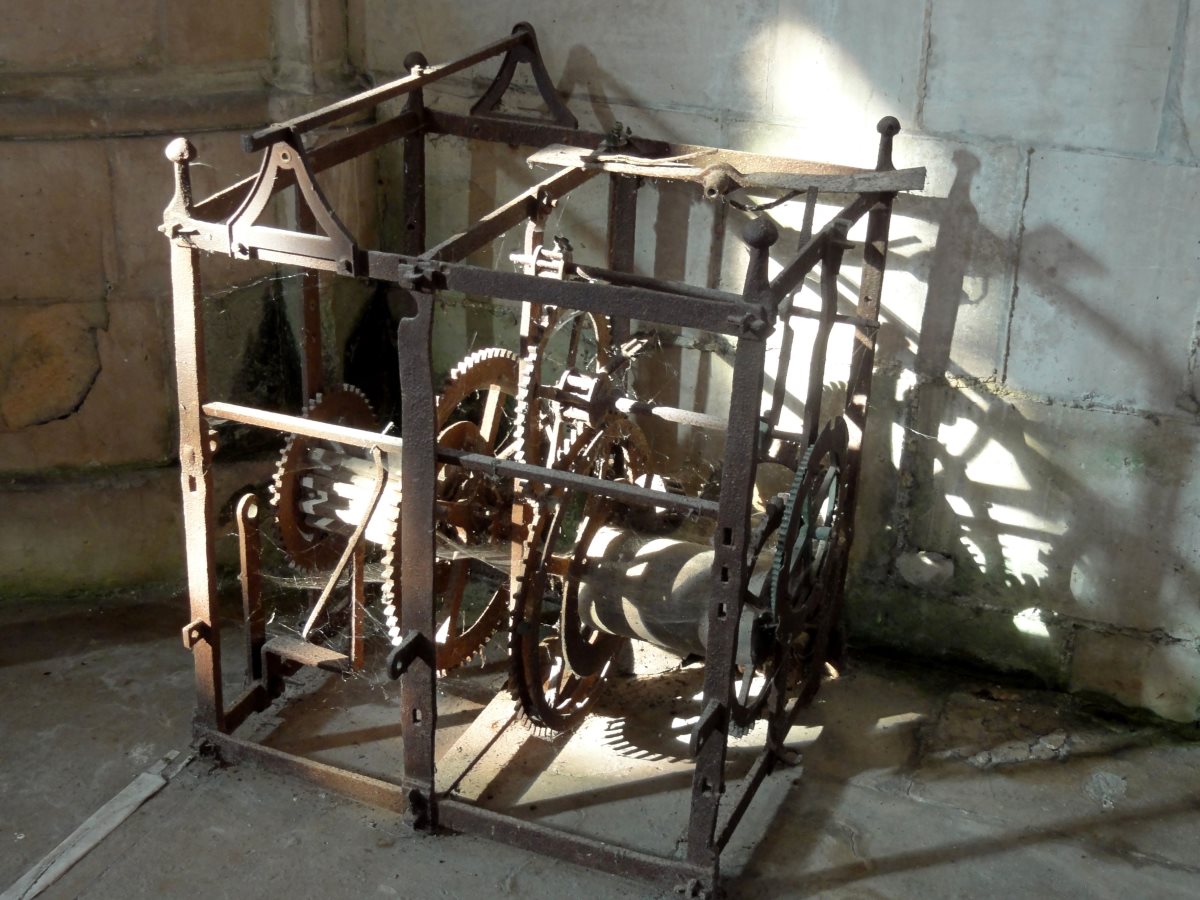

History shifted, it must be said, to meet the needs of religious and political power holders. The first astronomical clocks were installed in monasteries and on cathedral towers, with the aim of organizing prayer times – and, by extension, the lives of the faithful. Lords and kings quickly seized this great power. One of the first public clocks, designed by Henri de Vic, was installed at the Palais de la Cité in Paris, at the request of Charles V, in 1370. The monarch also ordered that all clocks in the kingdom be set to this one, a way of asserting the supremacy of temporal power over the spiritual power of the clergy.

The Era of Development

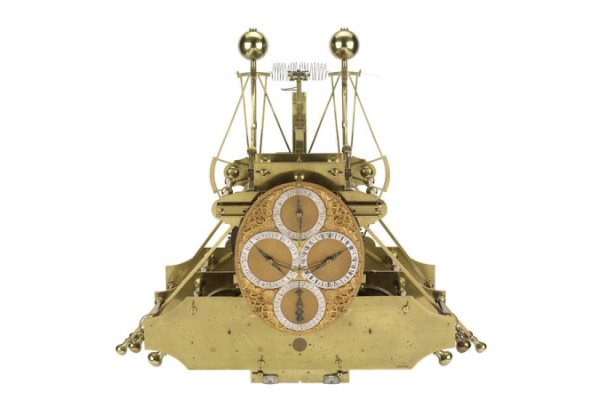

From then on, the advancement of watchmaking techniques accelerated. Mechanisms miniaturized, moving from towers to tables, notably with the spring-driven clock in 1430 and Julien Coudray’s ‘portable’ clocks, made for Francis I in 1518. Thanks to goldsmithing, French watchmaking transformed into the production of objects as refined as they were practical, true jewels whose purpose was no longer solely to capture time. Models still had a single, imprecise hand until the adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1582, with its division of the day into two twelve-hour periods, facilitated the manufacture of dials. Subsequently, the first complication watches emerged, designed to impress monarchs and courtiers, who were the most frequent patrons of master watchmakers.

A rumor began to spread from neighboring Switzerland, where a true mechanical watchmaking industry developed from the late 15th century. French artisans, like Thomas Bayard from Lorraine, appeared everywhere, but they crossed the border to learn their craft from our neighbors. This is because, in the Swiss Jura, watchmaking was already more than a craft: it was an art in its own right.

France then began to adopt a position that would remain valid for centuries: not only did its best watchmakers tend to emigrate (it was in England that De Beaufré designed the first ruby watch in 1704, giving British watchmaking a head start for quite some time), but failing to ‘produce’ great artisans, the country focused primarily on attracting them from abroad. Thus, invited by Regent Philippe d’Orléans, Henry de Sully arrived from London in Paris and founded a watchmaking manufacture in Versailles in 1718.

The creation of the Academy of Sciences by Colbert in 1666, the new prominence given to French watchmaking, and the construction of the Paris Observatory would only marginally alter this status as a ‘host’ country for watchmaking. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 worsened matters: Protestant watchmakers fled to England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, creating a tremendous exodus of talent. French watchmaking would then, most certainly, have long lost its hard-won position, had the Age of Enlightenment and its innovations not come to save its precious mechanisms.

From the Age of Enlightenment to Modern French Watchmaking

A major period for French watchmaking, the Age of Enlightenment benefited from prodigious advancements thanks to its best representatives, particularly in clockmaking: Julien Le Roy, then Pierre Le Roy, Jean-Antoine Lépine, Louis Dauthiau, or Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (yes, the inventor of the character Figaro the barber!) designed or perfected components, escapements, or astronomical clocks. Public clocks proliferated, manufactured by the brothers Jean-André and Jean-Baptiste Lepaute.

Clock production remained relatively low, and orders were limited to those from the Court. This did not prevent Paris from being, for a time, ‘the place to be’ for watchmakers. Ferdinand Berthoud provided invaluable assistance to marine chronometers, while the great Abraham-Louis Breguet, inventor of the perpetual watch, died in Paris after acquiring French nationality.

The Revolution somewhat changed the situation by relocating the vital center of French watchmaking: it was in Besançon, Franche-Comté, that master watchmakers, driven from their homes, settled, making the city the country’s leading watchmaking hub. Laurent Mégevand founded the Manufacture d’Horlogerie Française there. By the end of the 19th century, up to 90% of French watches were produced there, in some 400 workshops; and it was thanks to this surge that French watchmaking then managed to rank second globally in this art, just behind Switzerland.

This relocation, and its global success, demonstrate a distinctly French will to withstand adversity and bounce back stronger in the eye of the storm. Nothing seemed capable of burying French watchmaking… including quartz watches, which flooded in from Japan starting in the 1970s. It must be said that quartz technology originated from patents filed by a French engineer, Marius Lavet! These patents, registered in 1949, would be exploited by the world’s largest watch brands.

And today? After a gloomy period during the 70s and 80s, France managed to reposition itself in watchmaking, bringing its most prestigious brands into the fray. Major players in the sector have established themselves in niche markets, most often linked to fashion and the luxury industry; while component manufacturers have gradually gained global renown. The proof: 50% of the workforce in Swiss workshops is reportedly French. Today, the sector still accounts for 3,700 jobs spread across 85 companies (a large part of which are in the Doubs region) that generate annual revenues oscillating between 250 and 300 million (according to Ecostat). French watchmaking has therefore never stopped turning its gears.

Great French Watchmakers and Inventors

Here is a selection of watchmakers and inventors who contributed to writing the history of French watchmaking (in chronological order):

- Henri de Vic

- Julien Coudray

- Julien Le Roy

- Pierre le Roy

- Jean-Antoine Lépine

- Louis Dauthiau

- Jean-André Lepaute

- Jean-Baptiste Lepaute

- Henri Lepaute

- Auguste-Lucien Vérité

- Frédéric Japy

- Marius Lavet

- François-Paul Journe

- Richard Mille

- Edmond Jaeger

- Frédéric Boucheron

- Robert Greubel

- Christophe Claret

Major French Brands

Although the watchmaking world is currently dominated by Swiss manufacturers, French brands have successfully positioned themselves in the luxury sector, capitalizing on the rich history of French watchmaking. Thus, heritage brands (L. Leroy, Lip, Yema) are outpaced by brands from major global luxury groups (Cartier, Dior, Hermès). However, other players are making their mark in more specialized segments, such as military watches (Mer Air Terre) or watches designed for adventure (Patton).

Rare, however, are timepieces manufactured entirely in our country; only Pequignet offers 100% made-in-France watches.