At all times, human beings have expressed the desire to measure the flow of time. In this tireless quest, which led them to design modern clocks and watches, the sundial was the very first step, based on the path of our star shining in the sky to determine the time of day. Here is the history.

The first instrument for measuring time

Can we only imagine what was the invention of the sundial? With a rod and a graduated surface, the Ancients had found the most accurate method of their time to know the time of day; and they had the idea of observing the course of the solar star in our sky. Admittedly, this system could only work during the day, which limited its use. But the sundial was only supplemented by two mechanisms: the clepsydra and the hourglass, which they did not know how to calculate the hours, but “only” to measure the durations.

Doubtless the Egyptians already knew about the sundial, but no description has reached us. Other writings mention the use of this instrument: the Bible refers to the sundial possessed by Ahaz, king of Judah, in Jerusalem (8th century BC), Pliny the Elder evokes the one invented by the Greek Anaximander (6th century BC), and Herodotus attests to the use of gnomon among the Babylonians (around the 5th century BC), a usage that probably goes back to a much older invention, perhaps transmitted to the Egyptians in very remote times (2nd millennium BC). Using a gnomon to establish the height of the sun, the Eratosthenes Greek used it to demonstrate the roundness of the Earth.

But among the primitive sundials, it is the one created by Bérose, in Greece, that we know best. In the third century BC, the Chaldean had invented a vertical dial composed of a hollow hemisphere, turned towards the ground, and endowed, in the center of its cavity, with a button whose shadow, under the sun, marks the hours on the walls of the half-sphere. This type of dial has a name: the scaphé (“boat”).

In Europe, churches and monasteries appropriate the measure of time. The canonical dial, which emerged in the seventh century, is used to indicate to members of the religious community the beginning of liturgical acts; the problem of nocturnal hours will be bypassed with the help of the fire clocks. As for the (questionable) precision of these horizontal sundials, installed perpendicular to the walls of churches, abbeys and monasteries, it matters little. Not because the approximation would be acceptable, but because the Church is strong in imposing this calculation of hours as perfect.

The sundial, in fact, lacks precision. The fault at an hour that is not constant throughout the year. For the ancients, the interval between the sunrise and sunset is always twelve hours, whatever the time of the year – this is how dials of gnomons are graduated twelve times, distances equal. Now, according to the distance between the star and the Earth, the duration of the days grows and shrinks. So the antique dials indicate “unequal hours”, or “temporary”, varying according to the place and the season.

It will be necessary to wait for the invention of the inclined style to move to diagrams displaying equal hours. The inclination of the traditional stick stems from an awareness that dates back to the fifteenth century: the fact that the Earth revolves around the Sun. In a sense, the effectiveness of the inclined style, also called “polar”, has helped to demonstrate the veracity of the theses supported by scholars such as Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo: it was found that by tilting the style to make it parallel at the axis of the planet, the measurement of the hours became exact …

The appearance of clocks towards the end of the 14th century does not immediately bury the sundial. On the contrary, the two instruments become complementary: the sundial, in the now inclined style, is able to measure the time with a certain accuracy; and the clock can keep that time. This duo will have beautiful hours in front of him, before the increasing precision of the mechanisms relegates the sundial to the shelves of museums.

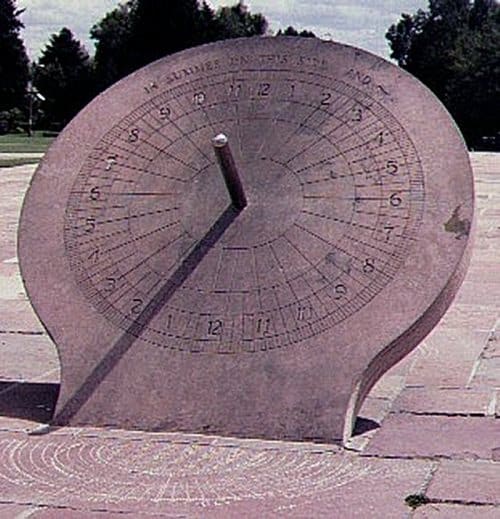

How a sundial works: the gnomon

The operation of the sundial is based on that of another instrument: the gnomon, an astronomical tool whose length and direction of shadow are used to point the hours drawn on a flat and horizontal surface. The gnomon is the whole device comprising the stem, planted or fixed, always vertically, bearing the name “style”, and the support on which it is placed – in a base or directly in the ground.

In itself, the gnomon aims to establish the height of the sun in the sky, always through its projected shadow. Originally a simple stick planted vertically in the ground, known to the Greeks and Chaldeans, he is at the origin of the science of sundials, which is called gnomonic. In short, the gnomon is the ancestor of the “modern” sundial reinvented by the Babylonians and Greeks.

How a sundial works: the division of the hours

The principle of gnomon applies very simply to the sundial: the shadow of the style is projected on divisions created artificially on the flat surface, indicating the flow of hours. The shadow follows the course of the sun in the sky and gradually passes over each division, like the needle on the dial of a watch.

The typical sundial is divided into twelve hours, which range from sunrise to sunset. But even with the later inclination of the style, the dial keeps its two main drawbacks: it only indicates the local time, which changes according to the longitude … and it remains subject to the vagaries of the weather!

Français

Français