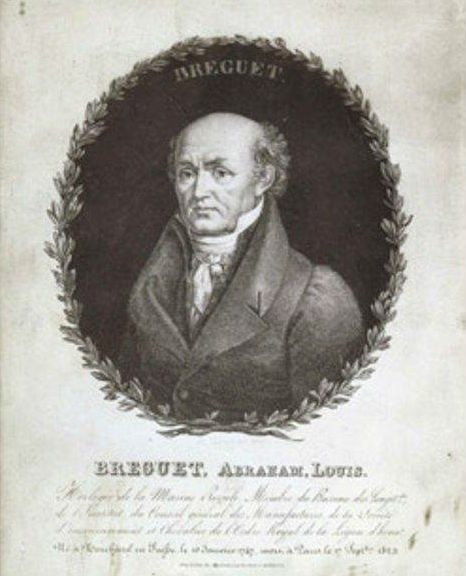

The art of watchmaking is, above all, an art of precision. And no one embodies this quest for accuracy and technical absolute better than the celebrated watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet. He elevated time measurement to an unprecedented level, and, in doing so, allowed watches and clocks to fully enter the era of modernity.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, the Man who Elevated Watches

Abraham-Louis Breguet, the Man who Elevated Watches

Aside from the Tourbillon, which he invented in 1801, Abraham-Louis Breguet was never one for grand displays. He was not as flamboyant as Ferdinand Berthoud, whom he succeeded as official watchmaker to the Royal Navy, nor as stubborn as John Harrison, with whom he shared the distinction of designing marine chronometers. Breguet was a man of discreet inventions, of silent advancements. Yet, quietly, his subtle steps profoundly changed the conception of watchmaking, paving the way for the modern developments of timepiece mechanisms.

Abraham-Louis Breguet was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on January 10, 1747, into a watchmaking family. His calling was thus almost a given. However, he soon left his family to move to France, specifically to the royal court in Versailles, where he furthered his apprenticeship under the guidance of Jean-Antoine Lépine and, especially, Berthoud, who at the time illuminated the Parisian watchmaking scene with his talents as a teacher and educator.

It was on Quai de l’Horlogerie, in Paris, that Breguet set up his workshop. It was 1775, and the young man was only 28 years old. It would take him less than ten years to launch his first inventions (such as the gong-spring for repeating watches), achieve the rank of master watchmaker (in 1784), and gain recognition from Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette for his truly remarkable creations. In 1786, the government sought his advice for a royal watchmaking manufacture that the king planned to build.

The Revolution forced him to seek refuge in Switzerland, but he returned to Paris in 1792 and obtained French citizenship. His reputation continued to grow when he submitted his candidacy to the Academy of Sciences, in the mechanical arts section (though he would only be admitted in 1816), before winning a gold medal at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products in 1798. Appreciated by Bonaparte, who bought three pieces from him, Breguet alternated between designing new mechanisms – such as the Tourbillon regulator, for which he filed the patent on June 26, 1801 – and creating unique pieces at the request of wealthy and powerful patrons, notably a famous wristwatch made for the Queen of Naples.

Also passionate about marine chronometers, for which he created a double-barrel model in 1815, Abraham-Louis Breguet attained the title of official watchmaker to the Royal Navy following the death of his former teacher, Berthoud. He wrote a booklet of Instructions on the Use of Marine Watches and also concerned himself with astronomy, designing an eyepiece for observation telescopes. In parallel, his importance at court continued to grow: this was the period when he was appointed a member of the Bureau des Longitudes, admitted to the Academy of Sciences, and awarded the Legion of Honor by Louis XVIII.

Having reached the pinnacle of his art and renown, Breguet passed away on September 17, 1823, in Paris, leaving the succession of his business to his son Louis-Antoine.

Precise and Precious Inventions

Precise and Precious Inventions

Less flamboyant than some of his peers, Abraham-Louis Breguet first built his reputation on his extraordinary ability to improve existing mechanisms, as if they were merely awaiting his genius to be perfected. His work on the perpetual watch, in particular, earned him great credit in the watchmaking world.

When he dedicated himself to his own inventions, it was in mechanical precision that he worked wonders. Examples include:

- In 1783, the gong-spring for repeating watches

- In 1790, the pare-chute (shock protection system), which, as its name suggests, is designed to absorb the shocks to which timepieces are subjected.

- In 1795, the Breguet overcoil

- In 1799, the tact watch

- In 1801, the Tourbillon

- In 1810, the wristwatch

- As well as numerous particularly precise escapements

To this non-exhaustive list, we can add: marine chronometers, astronomical clocks, metallic thermometers, etc.

Breguet: Always a Step Ahead

If only one invention developed by Abraham-Louis Breguet were to be remembered, it would certainly be the Tourbillon. Breguet sought to design a mechanism to balance the various parts of the watch. Until then, a timepiece, by default, was subject to the influence of gravity in the form of slight chronometric deviations. The Tourbillon was a rotating system that carried the entire escapement-balance assembly within a mobile cage, thereby compensating for the effects of terrestrial gravity and mitigating variations inherent in all human activity. Since its patenting in 1801, the Tourbillon, subsequently improved in many ways, has remained an absolutely mythical invention.

The Tourbillon was the embodiment of Breguet’s own ambition: to achieve perfection in the precision of watchmaking mechanisms. In parallel, the master paved the way for the era of grand horological complications, offering posterity a masterpiece of precision and complexity: watch no. 160, known as the “Marie-Antoinette”.

Throughout his career, Abraham-Louis Breguet revolutionized many aspects of watchmaking, with a discretion matched only by his humility. Through his talent, the art of watchmaking primarily became an art of mechanical and temporal precision.