Gnomon, sundial, clepsydra, or hourglass… Since the world began, Man has sought to circumscribe the inexorable flow of time, with the aim of measuring its intervals for his use. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the narrative of time measurement gives way to a true history of watchmaking, when the first mechanisms were installed on bell towers and belfries. This was the era of the medieval clock and the birth of mechanical watchmaking, which paved the way for the modern conception of time.

The Medieval Clock: a Matter of Belief

The Medieval Clock: a Matter of Belief

Emmanuel Poulle, in “For a Typology of Medieval Astronomical Watchmaking” (to be read in its entirety here) notes that watchmaking experienced extraordinary development in the 14th century. He adds that its importance can be perceived by observing the rise in the use of the term “clock,” now used to designate no longer the various time-measuring instruments (gnomon and other clepsydras), but rather clocks in the sense we understand them today.

In its early days, mechanical watchmaking, like the “simple” measurement of time before it, was a matter for churchmen: it was the monks who imported the fire clock with the aim of organizing the nocturnal canonical hours, and it was still the clergy who offered high-level technicians the opportunity to design and build the first mechanical clocks to install them on the bell towers and towers of their churches. Sometimes, these were astronomical clocks, capable of measuring the sun’s course in the sky.

- The chamber clock, or alarm clock: it was intended for the cell of the clock guardian, in the abbey or monastery, and would ring a bell, indicating to the abbot that it was time for prayer.

- The bell tower or tower clock: placed high up, in monastic establishments or churches, it automatically set in motion the large bell signaling the hour of prayer, this same bell that the attendant had to activate after being prompted by the chamber clock.

When Time Measurement Becomes Mechanical

When Time Measurement Becomes Mechanical

The medieval clock represents a significant change compared to the time-measuring instruments used until then: by its nature, due to the fact that it involves a hammer striking a bell, it introduced a new logic. It was no longer enough to perceive the passage of time; it was also necessary to inform the community about the time for devotions, and for this, to develop systems that could strike the hours.

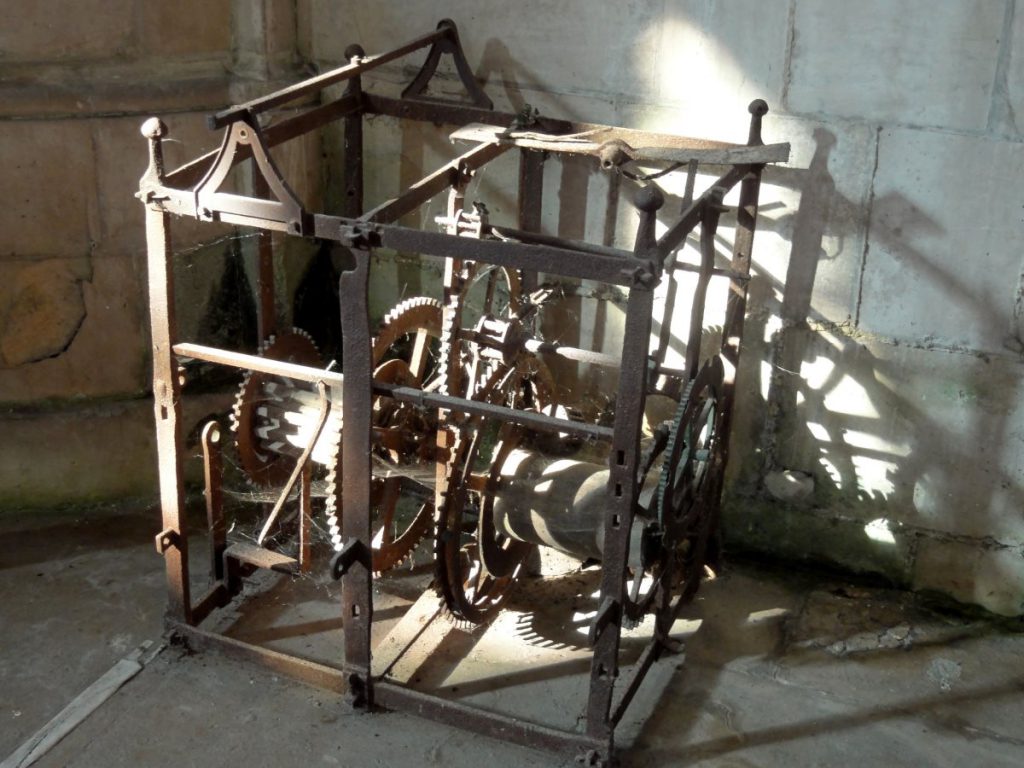

The medieval clock is thus the result of a monastic necessity materialized in the form of a revolutionary invention, albeit in its primitive form: the escapement, whose purpose is to control how the driving force is released into the clock. A mechanical clock can thus operate for hours, thanks to the control of a falling weight. This crucial innovation is nothing other than the birth, strictly speaking, of the mechanisms that would pave the way for modern watchmaking.

From then on, large clocks were installed everywhere in Europe at the top of bell towers and belfries. By striking the equal hours, they disseminated a new perception of time. Church towers were transformed into clock towers; bell towers became campaniles; astronomical clocks adorned themselves with astonishing movements and original mechanisms; the passage of time was transformed into a public service, offered to everyone within the community.

The Watchmaker’s Profession During the Medieval Period

The Watchmaker’s Profession During the Medieval Period

While one cannot literally speak of a “watchmaker” at that time, medieval watchmaking nevertheless had its skilled technicians, and until the 15th century, it was indeed a profession that slowly took shape, bringing together numerous technical skills in service of a common purpose. Initially, however, watchmaking remained a secondary activity for these goldsmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths, and ironworkers who experimented with and invented original mechanisms; they assisted astronomers, geometers, and philosophers who sought to capture duration in new temporal machines (see on this page).

The fragility of the mechanisms requiring constant attention, the first true profession related to medieval watchmaking was that of a guardian: who was permanently responsible, in the town or village, for the maintenance of the local timepiece. Most often, the manufacturers themselves took on this task: traveling with all their tools and personnel, including a forge, they built and installed clocks on public monuments, then returned at regular intervals to ensure their operation, within a restricted geographical area.

However, very early on, the first watchmakers worthy of the name appeared: the Englishman Richard of Wallingford (around 1330) and the Italian Giovanni Dondi (second half of the 14th century), both of whom became masters in the art of building astronomical clocks. Building on these two precedents, some watchmakers gained a certain renown; but it was necessary to wait until the end of the 15th century and the official status granted by Louis XI to royal watchmakers for mere technical skill to transform into a recognized profession, thereby marking the end of medieval watchmaking and the beginning of modern watchmaking.