[:fr]Gnomon, cadran solaire, clepsydre ou sablier… Depuis que le monde est monde, l’Homme a cherché à circonscrire l’écoulement inexorable du temps, dans le but d’en mesurer les intervalles à son usage. Vers la fin du Moyen Âge, le récit de la mesure du temps fait place à une véritable histoire de l’horlogerie, lorsque les premiers mécanismes s’installent sur les clochers et les beffrois. C’est l’époque de l’horloge médiévale et de la naissance de l’horlogerie mécanique, qui ouvrit la voie à la conception moderne du temps.

L’horloge médiévale : une affaire de croyance

L’horloge médiévale : une affaire de croyance

Emmanuel Poulle, dans « Pour une typologie de l’horlogerie astronomique médiévale » (à lire dans son entier ici) note que l’horlogerie connaît, au XIVe siècle, un développement extraordinaire. Il ajoute que l’on peut percevoir son importance en observant la hausse de l’usage du terme « horloge », désormais utilisé pour désigner non plus les divers instruments de mesure du temps (gnomon et autres clepsydres), mais bien des horloges au sens où on l’entend aujourd’hui.

Dans ses premiers temps, l’horlogerie mécanique, comme avant elle la « simple » mesure du temps, est affaire d’hommes d’Église : ce furent les moines qui importèrent l’horloge à feu dans le but d’organiser les heures canoniales nocturnes, et ce sont les religieux, encore, qui offrent à de hauts techniciens l’occasion de concevoir et de réaliser les premières horloges mécaniques afin de les installer sur les clochers et les tours de leurs églises. Parfois, il s’agit d’horloges astronomiques, capables de mesurer la course du soleil dans le ciel.

De fait, les premières horloges européennes ont été conçues moins pour donner l’heure que pour la sonner. On en relève traditionnellement deux types :

De fait, les premières horloges européennes ont été conçues moins pour donner l’heure que pour la sonner. On en relève traditionnellement deux types :

- L’horloge de chambre, ou réveille-matin : elle est destinée à la cellule du gardien de l’horloge, dans l’abbaye ou le monastère, et fait tinter une cloche indiquant à l’abbé qu’il est l’heure de la prière.

- L’horloge de clocher ou de tour : placée en hauteur, dans les établissements monastiques ou les églises, elle met automatiquement en branle la grosse cloche signalant l’heure de la prière, cette même cloche que le préposé devait activer après y avoir été invité par l’horloge de chambre.

Quand la mesure du temps devient mécanique

Quand la mesure du temps devient mécanique

L’horloge médiévale représente un changement important en regard des instruments de mesure du temps utilisés jusque là : de par sa nature, du fait qu’elle impose un geste de frappement de marteau sur une cloche, elle embarque une nouvelle logique. Il ne suffit plus de percevoir le temps qui s’écoule ; il faut encore informer la communauté quant au moment des dévotions, et pour cela, élaborer des systèmes qui puissent sonner les heures.

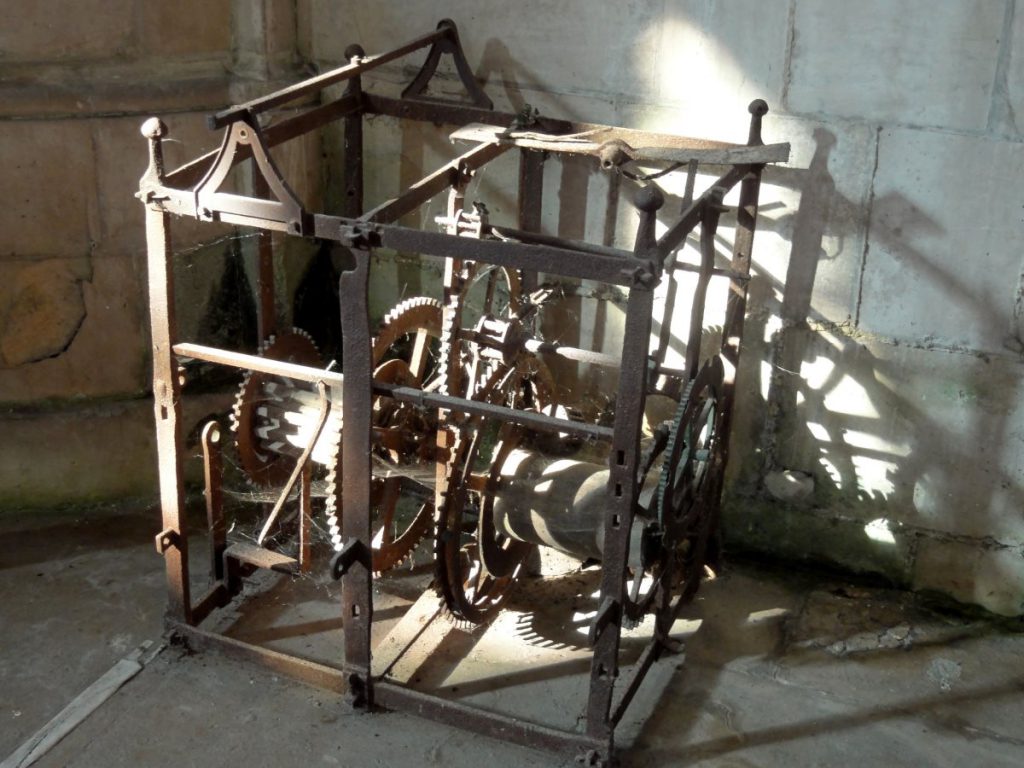

L’horloge médiévale est ainsi le résultat d’une nécessité monastique matérialisée sous la forme d’une invention révolutionnaire, dans sa forme certes primitive : l’échappement, qui a pour objet de maîtriser la manière dont la force motrice s’échappe vers l’horloge. Une horloge mécanique peut ainsi fonctionner des heures durant, grâce au contrôle de la chute d’un poids. Cette innovation capitale n’est rien d’autre que la naissance, à proprement parler, des mécanismes qui ouvriront la voie à l’horlogerie moderne.

Dès lors, partout en Europe, on installe des horloges de grande taille au sommet des clochers et des beffrois. En sonnant les heures égales, elles diffusent une perception nouvelle du temps. Les tours des églises se transforment en tours-horloges ; les clochers deviennent des campaniles ; l’horloge astronomique se pare de mouvement étonnants et de mécanismes originaux ; l’écoulement du temps se métamorphose en un service public, offert à tous au sein de la communauté.

Le métier d’horloger durant la période médiévale

Le métier d’horloger durant la période médiévale

Si l’on ne peut pas alors parler littéralement d’ « horloger », l’horlogerie médiévale possède néanmoins ses techniciens de valeur, et jusqu’au XVe siècle, c’est bel et bien une profession qui prend forme doucement, agrégeant de nombreuses compétences techniques au service d’un même dessein. Au départ, l’horlogerie reste toutefois une activité annexe pour ces orfèvres, serruriers, forgerons et ferronniers qui expérimentent et inventent des mécanismes originaux ; ils viennent en aide aux astronomes, géomètres et philosophes qui cherchent à emprisonner la durée dans de nouvelles machines temporelles (voir sur cette page).

La fragilité des mécanismes contraignant à une attention constante, le premier véritable métier lié à l’horlogerie médiévale est celui de gardien : il prend en charge, à demeure, dans la ville ou le village, la maintenance du garde-temps local. Le plus souvent, ce sont les fabricants qui se chargent de cette tâche : se déplaçant avec la totalité de leurs outils et de leur personnel, forge comprise, ils réalisent et installent les horloges sur les monuments publics, puis reviennent à intervalles réguliers afin d’en assurer le fonctionnement, sur un territoire géographique restreint.

Mais très tôt, on assiste à l’apparition des premiers horlogers dignes de porter ce nom : l’Anglais Richard de Wallingford (autour de 1330) et l’Italien Giovanni Dondi (seconde partie du XIVe siècle), qui passent tous deux maîtres dans l’art de construire des horloges astronomiques. À partir de ces deux précédents, quelques horlogers acquièrent une certaine renommée ; mais il faut attendre la fin du XVe siècle et le statut officiel octroyé par Louis XI aux horlogers royaux pour que la seule technicité se transforme en une profession reconnue, marquant, de fait, la fin de l’horlogerie médiévale et le début de l’horlogerie moderne.

[:en]Gnomon, sundial, clepsydra or hourglass … Since the world is world, Man has sought to circumscribe the inexorable flow of time, in order to measure the intervals for its use. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the story of the measurement of time gives way to a true history of watchmaking, when the first mechanisms are installed on the steeples and belfries. It is the era of the medieval clock and the birth of mechanical watchmaking, which opened the way to the modern conception of time.

[:en]Gnomon, sundial, clepsydra or hourglass … Since the world is world, Man has sought to circumscribe the inexorable flow of time, in order to measure the intervals for its use. Towards the end of the Middle Ages, the story of the measurement of time gives way to a true history of watchmaking, when the first mechanisms are installed on the steeples and belfries. It is the era of the medieval clock and the birth of mechanical watchmaking, which opened the way to the modern conception of time.

The medieval clock: a case of belief

Emmanuel Poulle, in « For a typology of medieval astronomical watchmaking » (to read in its entirety here) notes that the clockmaking knows, in the XIVe century, an extraordinary development. He adds that we can perceive its importance by observing the increase in the use of the term « clock », now used to designate not the various instruments of time measurement (gnomon and other clepsydres), but many clocks in the sense where we hear it today.

In its early days, mechanical watchmaking, as before it the « simple » measure of time, is a matter of men of the Church: it was the monks who imported the clock to fire in order to organize the canonical hours nocturnal, and it is the religious, again, who offer high technicians the opportunity to design and realize the first mechanical clocks to install on the steeples and towers of their churches. Sometimes they are astronomical clocks, able to measure the sun’s path in the sky.

In fact, the first European clocks were designed less to tell the time than to ring it. There are traditionally two types:

- The room clock, or alarm clock: it is intended for the cell of the watchman of the clock, in the abbey or the monastery, and makes a bell ringing indicating to the abbot that it is time for prayer.

- The clock tower or tower: placed high up, in monastic establishments or churches, it automatically sets in motion the big bell signaling the time of prayer, the same bell that the attendant had to activate after being invited by the bedroom clock.

When the measurement of time becomes mechanical

The medieval clock represents a significant change in the time measurement instruments used so far: by its nature, because it imposes a gesture of hammering on a bell, it embodies a new logic. It is no longer enough to perceive the time that elapses; the community still needs to be informed about the timing of the devotions, and to do this, develop systems that can sound the hours.

The medieval clock is thus the result of a monastic necessity materialized in the form of a revolutionary invention, in its certainly primitive form: the escapement, whose object is to control the way in which the driving force escapes towards the ‘clock. A mechanical clock can work for hours, thanks to the control of the fall of a weight. This capital innovation is nothing more than the birth, strictly speaking, of the mechanisms that will pave the way for modern watchmaking.

From then on, throughout Europe, large clocks were installed at the top of bell towers and belfries. By sounding the same hours, they broadcast a new perception of time. The towers of churches are transformed into clock towers; the steeples become campaniles; the astronomical clock is adorned with astonishing movements and original mechanisms; the passage of time is transformed into a public service, offered to everyone in the community.

The watchmaking profession during the medieval period

If one can not then speak literally of « watchmaker », medieval watchmaking nevertheless has its valuable technicians, and until the fifteenth century, it is indeed a profession that takes shape slowly, aggregating many technical skills at the service of the same purpose. Initially, watchmaking remains an ancillary activity for these goldsmiths, locksmiths, blacksmiths and blacksmiths who experiment and invent original mechanisms; they help astronomers, geometers and philosophers who seek to imprison time in new temporal machines (see on this page).

The fragility of the binding mechanisms to a constant attention, the first real trade related to the medieval watchmaking is that of guardian: it supports, in residence, in the city or the village, the maintenance of the local timepiece. Most often, it is the manufacturers who take on this task: moving with all their tools and personnel, including forging, they make and install the clocks on public monuments, then come back at regular intervals to to ensure its operation, in a limited geographic area.

But very soon, we see the appearance of the first watchmakers worthy of this name: the Englishman Richard de Wallingford (around 1330) and the Italian Giovanni Dondi (second part of the fourteenth century), both masters in the art of building astronomical clocks. From these two precedents, some watchmakers acquire a certain renown; but it was not until the end of the fifteenth century and the official status granted by Louis XI royal watchmakers that the only technicality is transformed into a recognized profession, marking, in fact, the end of medieval watchmaking and the beginning of the modern watchmaking.

[:]

[:]