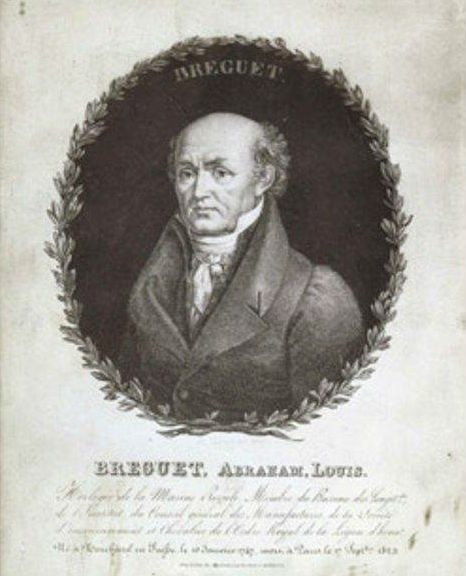

The art of watchmaking is above all an art of precision. And no one better embodies this quest for accuracy and absolute technique than the famous watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet. Man has raised the measure of time to a degree never before achieved, and in so doing has allowed watches and clocks to enter the era of modernity.

Abraham-Louis Breguet, the man who sublimated watches

Apart from the Tourbillon, which he invented in 1801, Abraham-Louis Breguet was never the watchmaker of the big splinters. He was not as flamboyant as Ferdinand Berthoud, whose successor he was as the Royal Navy’s watchmaker, nor as stubborn as John Harrison, with whom he had in common the design of marine chronometers. Breguet was the man of discreet inventions, silent advances. But, slowly, its small strides have contributed to a profound change in the conception of watchmaking, to pave the way for modern developments in the mechanisms specific to timepieces.

Abraham-Louis Breguet was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on January 10, 1747, into a watchmaking family. His vocation is almost obvious. But he soon abandoned his family to join France, and precisely the King’s court in Versailles, where he benefited from a development of his apprenticeship under the leadership of Jean-Antoine Lépine and, above all, from Berthoud, who then illuminated the scene. Parisian watchmaker because of his talents as a teacher and pedagogue.

It is Quai de l’Horlogerie, in Paris, where Breguet moved to open his studio. We are in 1775, the young man is only 28 years old. It will take him less than ten years to launch his first inventions (like the spring-stamp for the repeating watches), to reach the rank of master-watchmaker (in 1784), and to be spotted of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette for his creations quite remarkable. In 1786, the government sought his opinion for a royal watchmaking factory whose king planned the construction.

The Revolution forced him to take refuge in Switzerland, but he returned to Paris in 1792 and obtained French citizenship. His reputation continues to grow when he applies for the Academy of Sciences, in the mechanical arts section (he will enter however in 1816), before winning a gold medal at the Exhibition national product industry, in 1798. Appreciated by Bonaparte, who buys three pieces, Breguet alternates between the design of new mechanisms – and the regulator Tourbillon which he filed the patent June 26, 1801 – and the realization of parts unique at the request of rich and powerful sponsors, including a famous wristwatch made for the Queen of Naples.

Also passionate about marine chronometers, which he created in 1815 a model with double barrel, Abraham-Louis Breguet attains the title of watchmaker of the Royal Navy following the death of his former teacher, Berthoud. He writes a booklet on the use of marine watches and is concerned with astronomy, with the design of an eyepiece for observation glasses. In parallel, his importance to the court is growing: it is the time when he is appointed member of the office of Longitudes, received at the Academy of Sciences, and crowned the Legion of Honor for Louis XVIII.

Reaching the peak of his art and reputation, Breguet died on 17 September 1823 in Paris, leaving the estate of his business to his son Louis-Antoine.

Precise and valuable inventions

Less flamboyant than some of his colleagues, Abraham-Louis Breguet first built his reputation on his extraordinary ability to improve existing mechanisms, as if they were waiting for his genius to be sublimated. His work on the perpetual watch, in particular, gives him great credit in the world of watchmaking.

When he strikes up his own inventions, it is on mechanical precision that he does miracles. For example:

- In 1783, the spring-stamp for repeating watches

- In 1790, the fall arrest, which as its name suggests is intended to take the shocks to which the timepieces are subjected

- In 1795, the spiral Breguet

- In 1799, the tactful watch

- In 1801, the Tourbillon

- In 1810, the wristwatch

As well as many particularly precise exhausts

Let us add to this non-exhaustive list: marine chronometers, astronomical clocks, metal thermometers, etc.

Breguet: always one step ahead

If we had to keep only one invention developed by Abraham-Louis Breguet, it would certainly be the Tourbillon. Breguet then sought to design a mechanism to balance the different parts of the watch. Until then, a timepiece, by default, was influenced by gravity in the form of slight timing offsets. The Tourbillon was a rotation system that carried the escapement-pendulum assembly in a mobile cage, thus making it possible to compensate for the effects of Earth’s gravity, and to weight the variations inherent in all human activity. Since 1801 and its patenting, the Tourbillon, improved in many ways later, has remained an absolutely mythical invention.

The Tourbillon was the application of Breguet’s own ambition: to achieve perfection in the precision of watchmaking mechanisms. In parallel, the master opened the way to the era of great horological complications, offering posterity a must of precision and complexity: the watch n ° 160 called “Marie-Antoinette”.

Throughout his career, Abraham-Louis Breguet has revolutionized many aspects of watchmaking, with a discretion that was matched only by his humility. Through his talent, the art of watchmaking has become above all an art of mechanical and temporal precision.

Français

Français