Born thanks to the transfer of technology put in place by Swiss manufacturers in the second half of the nineteenth century, Japanese watchmaking has slowly freed itself from Swiss tutelage to produce its own timepieces. It is today shared between the two giants of the watch industry, Seiko and Citizen on one side, and a whole archipelago of independent workshops on the other, less known but able to attract the attention of amateurs of watches all over the planet.

History of Japanese watchmaking

As early as the end of the 19th century, Switzerland, through the Union Watch, organized a transfer of its watch and clock expertise to Japan, where a market is developing. And for good reason: after centuries of isolationism, the archipelago is opening up to international trade. The first counter was opened in Yokohama in 1863. Until the middle of the twentieth century, Japanese watchmakers settled in Swiss workshops where they were trained according to Swiss quality standards, before returning home to provide service after -Sale of major Western brands that, on the spot, are experiencing a great success, although their productions are mainly used for ceremonial jewelry. Japanese watchmaking has therefore started as a commercial partner of a Switzerland wishing to arrogate itself a market all the more extensive that from 1873, Japan adopts the sharing of days in 24 hours and that the demand for watches grows quickly.

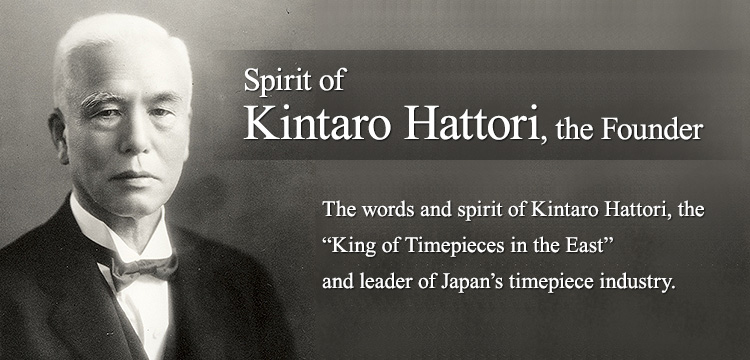

But the Japanese are not fooled, they know that this technology transfer has for first purpose the unilateral domination of Swiss watchmaking. That’s why local watchmakers, who have become experts themselves, are starting to develop the national watch industry. A first major trial was launched in 1891 with the founding of the Nippon Watch Manufacturing Co., whose production stops … four years later! This does not prevent the independents from offering their own models produced in small quantities, like those of Hattori Kintaro, who founded in 1892 the Seikosha Clock Factory, future Seiko.

The Japanese partner is gradually becoming a strong competitor, developing first class manufactures in the shadow of Switzerland. Local production is supplanting imports, boosted by significant innovations such as Seiko’s first wristwatch in 1913. The ravages of the Second World War will put a stop to this industrial development. But Japanese watchmaking is not dead, she just fell asleep; and its awakening, in 1947, is symbolized by the creation of the Japanese Watchmaking Association, which leads the country to launch a vast global export program of its watches and clocks.

The potential is there, but it really explodes during the 70’s thanks to the quartz revolution … and raises a tsunami that will fail to completely drown the entire competing industry. By producing electronic watches based on quartz technology, much cheaper to manufacture than mechanical timepieces, Japan dominates the planet and gives its watch industry a prominent place. An extraordinary success for a watchmaking that did not exist less than a century ago. And that has literally turned the tide: now, it is the Swiss watch industry that takes its example from its Japanese colleague in the field of electronic timepieces.

It should be noted, however, that long before the onslaught of quartz watches, the Japanese watch industry had gained market share at the expense of the Swiss, during this period between the end of the Second World War and the 1970s. mechanical watches, first with manual winding and then automatic a few times later, of a quality equal to or even superior to the Swiss production (for example in terms of sealing), and at prices with which the Helvetian workshops could not claim compete.

It is also towards a return to mechanics that the Japanese watchmaking is heading after its electronic flash, like the vast majority of Swiss manufacturers. The current market is divided between the general public, which leans towards quartz watches, and a community of collectors and aesthetes, which favors the high-end mechanical watch. The iconic example has been – and remains – the Grand Seiko, flagship of the famous brand since 1960. A shift towards luxury watchmaking that echoes, again, the Swiss example, as if history relations between Switzerland and Japan was something of a perpetual movement.

Japanese watchmakers

Japanese watchmakers remain little known to the general public. The names that stand out are most often those of the founders of the dominant brands.These include:

– Hattori Kintaro

– Kono Shohei

– Yosaburo Nakajima

– Hajime Asaoka

– Masahiro Kikuno

The big Japanese brands

The two giants of Japanese watchmaking are born of the important transfer of skills that began in the late nineteenth century between Switzerland and the Land of the Rising Sun. At the time, local watchmakers are primarily importers of Swiss brands, they contribute to install on the territory: Omega, Tissot, Zenith. Then, progressively, watchmakers develop their own timepieces, like Hattori Kintaro, the future heavyweight of Japanese watchmaking with the Seiko brand. It is the same for its main competitor, the other dominant figure of the sector: Citizen Watch Co., founded in 1918.

The strength of Japanese brands lies in their ambition for research and development. Among the creations due to Seiko include: the quartz watch in 1969 (the Astron), the LCD screen for shows in 1973, the first watch using a micro-alternator in 1988, the movement Spring Drive in 1999, the first shows a GPS in 2012. Less innovative, the rival Citizen can still justify the invention of Eco-Drive, a system built into its timepieces that transforms light into energy and stores it in a lithium battery -ion, allowing it to recharge alone.

In 1971, a third major player came to join the duo: this is the year when the calculator manufacturer Casio launched its first models of electronic watches, which met with great success. Today, Casio, like its competitors, is organizing its move upmarket to more luxurious timepieces, while remaining in the field of electronics.

The other segment of Japanese watchmaking is occupied by independent creators who are more and more noticed by the Swiss, such as Hajime Asaoka (former student of Philippe Dufour) or Masahiro Kikuno (member of the Academy of Independent Designers) .

Français

Français