L’histoire de l’horlogerie est celle d’une conquête millénaire, qui a vu le genre humain s’approprier petit à petit les territoires dévolus au Temps. Depuis l’invention des premiers mécanismes d’écoulement des durées jusqu’au développement des garde-temps les plus en pointe, aboutissements d’un savoir-faire mondial et millénaire, l’histoire de l’horlogerie s’apparente à une quête du Graal dans laquelle l’essentiel est moins la finalité que l’exploration des mystères du temps qui passe. Découvrez tout ce qu’il faut savoir sur ce guide.

[:fr]

L’histoire de l’horlogerie : les premiers temps

S’il est bien un secret que l’Homme a perpétuellement cherché à dompter, c’est bien celui du Temps. À la fois inconsistant et insaisissable, et pourtant terriblement concret pour nous autres humains qui nous voyons inéluctablement vieillir, le Temps a fasciné au moins autant que la nature divine du Monde. C’est pourquoi son histoire est au moins autant celle des horlogers célèbres que des mécanismes étonnants qu’ils ont livrés à l’humanité.

Ce n’est pas surprenant qu’il faille remonter jusqu’à l’Égypte antique, autour du XVe siècle avant J.-C., pour trouver trace du tout premier cadran solaire, un instrument d’une remarquable confection qui permet d’indiquer l’écoulement de la journée en suivant le parcours céleste de l’astre diurne, à l’aide d’un gnomon. L’existence de tels cadrans est ensuite attestée dans plusieurs régions du monde, et notamment en Grèce hellénistique.

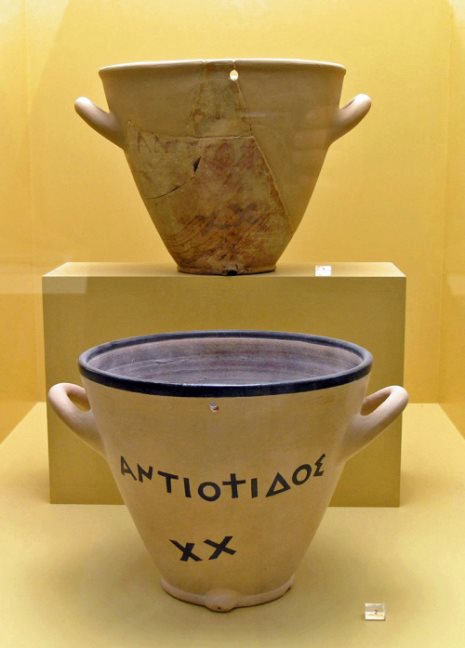

Une fois que l’homme s’est entiché de cet étrange projet – maîtriser l’intangible Temps – il conçoit des mécanismes de plus en plus évolués. Si le cadran solaire voit son fonctionnement assujetti à la présence effective du Soleil, d’autres instruments se proposent de mesurer des durées sans avoir à attendre que le bel Apollon daigne quitter son repère. C’est le cas de la clepsydre, ou horloge à eau, qui offre d’apprécier des durées brèves avec une précision plus que satisfaisante. C’est le cas également de l’horloge à feu, dont des traces de l’utilisation remontent jusqu’au VIe siècle avant notre ère, du côté de l’Extrême-Orient.

Des horloges aux montres

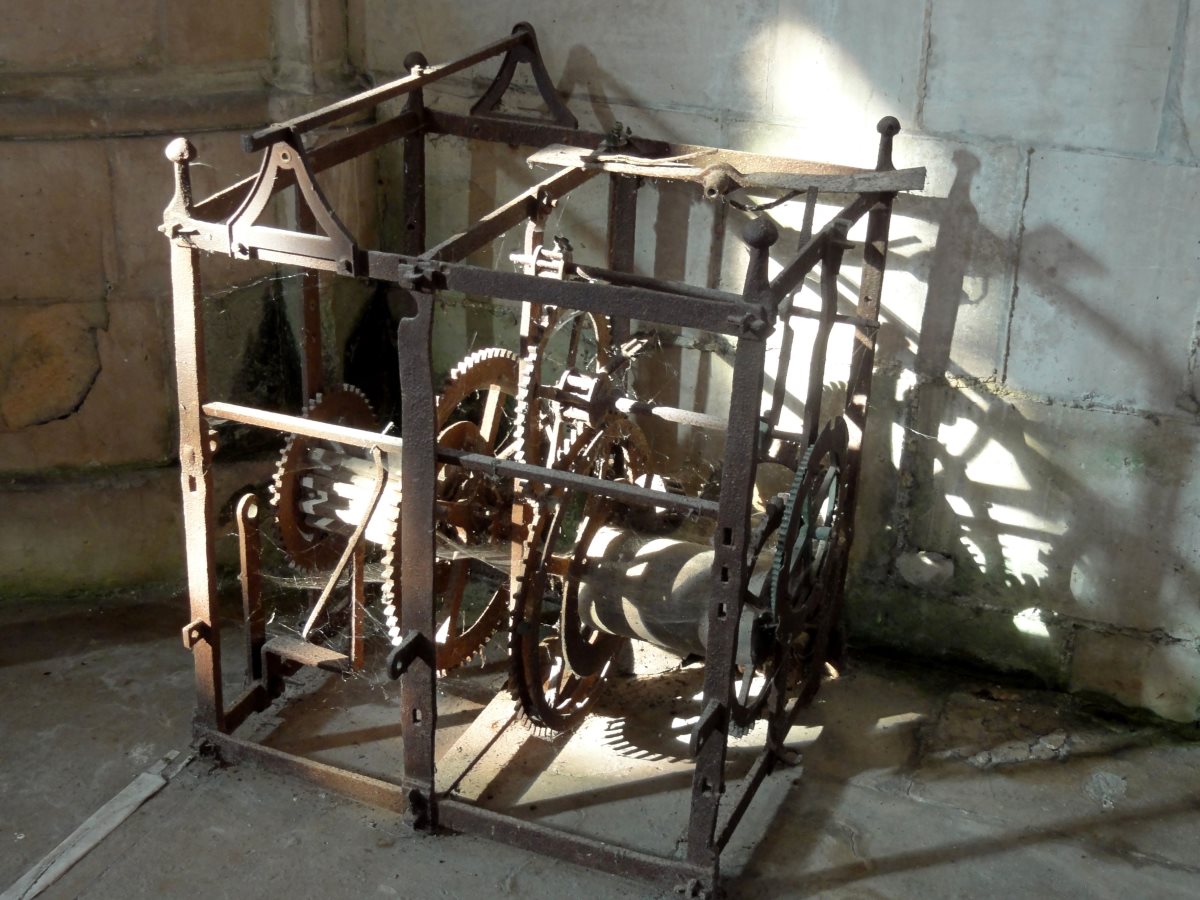

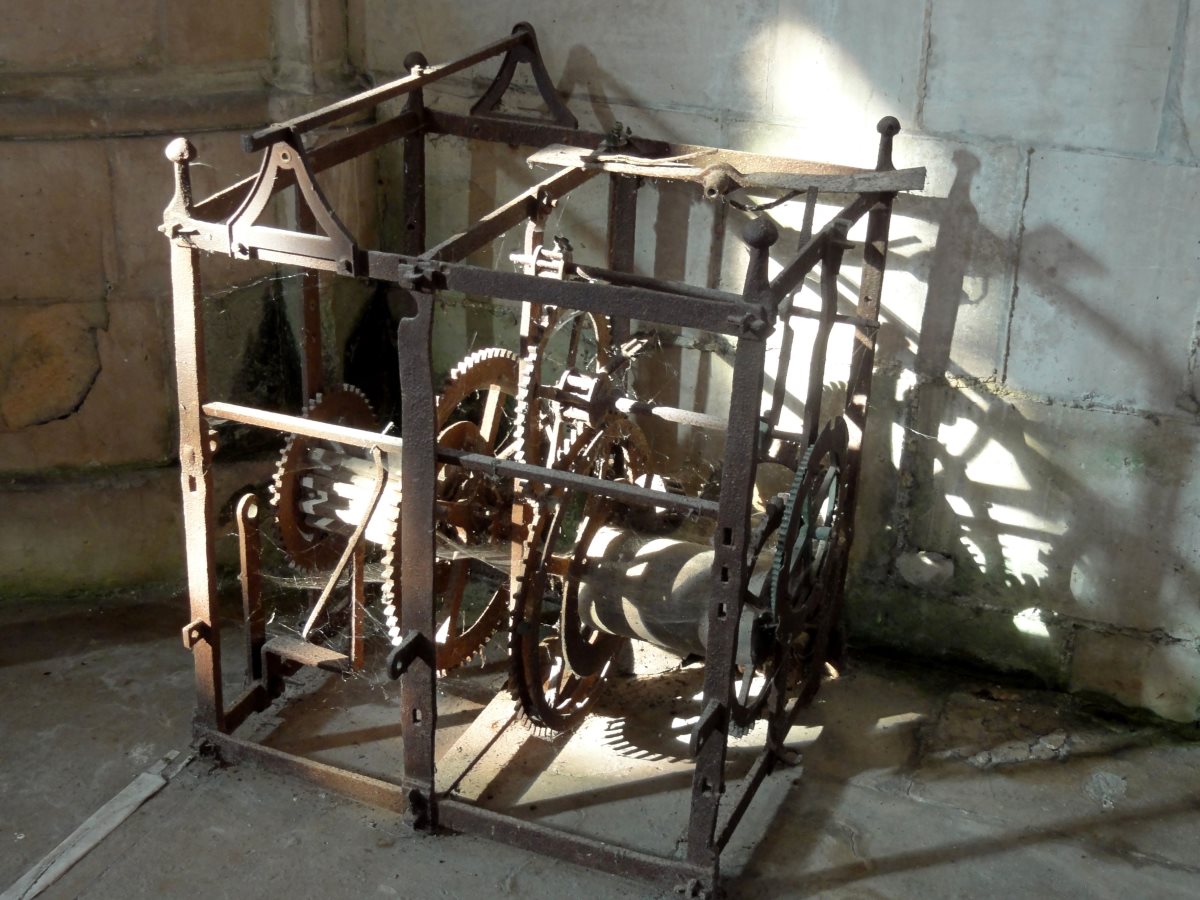

Aussi remarquables soient-ils, ces mécanismes restent forcément limités, les uns à la bonne volonté du Soleil, les autres à la seule mesure des durées plutôt qu’à la capture d’un Temps absolu. Il faut attendre le XIVe siècle pour que l’Europe médiévale fasse un bond en avant dans la manufacture des garde-temps, avec l’invention puis l’installation des premières horloges astronomiques, qui visent en même temps à informer sur les horaires des services religieux ou des événements publics, et à offrir une vision mécanique du système solaire, évidemment inspirée du modèle de Ptolémée.

S’ensuit une période cruciale de l’histoire de l’horlogerie, qui voit les artisans français, puis suisses, chercher à développer les systèmes existants et à les miniaturiser, jusqu’à les faire tenir sur les tables de l’aristocratie. L’horloge médiévale devient bientôt un objet de prestige, aussi raffiné que pratique, pensé moins pour capturer une portion du temps que pour décorer les intérieurs. Cette ambition de la miniaturisation va pousser jusqu’à la confection des premiers modèles de garde-temps à complications et des montres de poches, modèles imaginés pour impressionner les cours royales et pour conférer de la notoriété aux maîtres-horlogers. C’est là, au creux de l’Europe du Moyen Âge, que l’histoire de l’horlogerie devient, à proprement parler, l’histoire des montres.

De la Renaissance jusqu’à l’aube du monde moderne

La période de la Renaissance voit l’aboutissement de ce mouvement qui transforme les horloges en montres. C’est aussi à cette époque que le centre de gravité de l’horlogerie européenne se déplace progressivement du côté de la Suisse et de l’Angleterre, oscillant d’une nation à l’autre, tandis que la France, à la faveur de la révocation de l’Édit de Nantes, voit fuir une majeure partie de ses artisans horlogers les plus brillants. Genève et Londres ont beau être concurrentes en matière de garde-temps, elles ont contribué ensemble à la mise en route d’une histoire des montres modernes, en faisant entrer ces mécanismes dans l’ère de la précision.

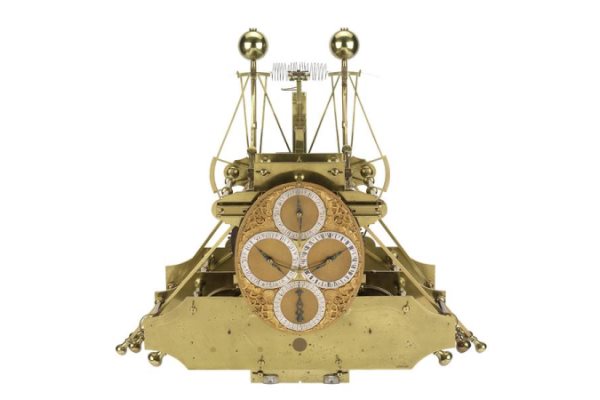

Mais sans doute l’histoire de l’horlogerie n’eût-elle pas été la même sans l’appétence des cours européennes pour les pendules de marine. Au XVIIe siècle, le monde est encore jeune et demande à être découvert. Même si les dangers des océans n’ont pas empêché de grands explorateurs de s’embarquer, tous les navigateurs de l’époque conviennent que les déplacements maritimes seraient bien plus aisés s’il leur était possible de calculer leur longitude à tout instant. Motivés par la promesse d’une reconnaissance nationale (et par la perspective d’une prime royale), les meilleurs esprits du temps s’attèlent à concevoir une horloge de marine parfaite. C’est la première étape d’une course à la précision mécanique qui ne s’arrêtera plus.

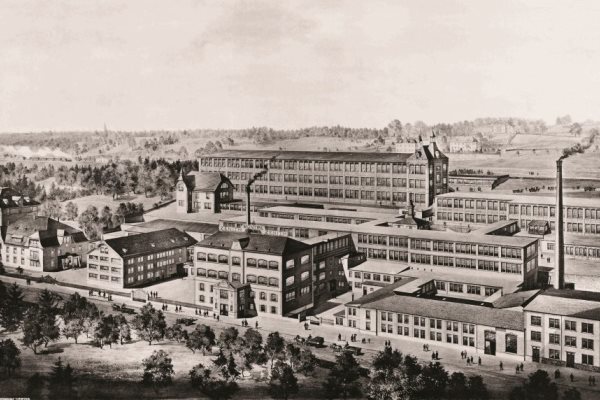

Comme de nombreux secteurs où l’invention s’allie au commerce, celui de l’horlogerie n’échappe pas à la vague d’industrialisation qui touche la planète au XIXe siècle. Avec la mécanisation du travail, rendue possible par le développement des machines-outils, et la division des tâches, l’Europe entre dans une période d’industrialisation de l’horlogerie. L’horlogerie du XIXe siècle tend vers la mécanisation, et nul ne peut s’y soustraire… Pas mêmes les artisans suisses qui s’engagent dans cette voie non sans y avoir été poussés par les États-Unis, où la Révolution industrielle de l’horlogerie a pris racine.

L’histoire des montres depuis le XXe siècle

L’apparition de la montre-bracelet détermine le moment de l’entrée dans l’horlogerie du XXe siècle. La montre à gousset, bijou fidèle des classes aisées, est petit à petit remplacée par des modèles qui s’attachent autour du poignet, jusqu’à ce que la fin du premier conflit mondial relègue la première à l’état d’antiquité. Désormais, le garde-temps se porte en bracelet et s’emmène partout – dans les voitures de course, dans les cockpits d’avion, et jusqu’aux points les plus extrêmes du globe, où les montres accompagnement fidèlement nos plus courageux explorateurs.

En passant de l’histoire des horloges à l’histoire des montres, la quête humaine du Temps a toujours conservé sa particularité artisanale : la conception des mécanismes se fait à la main, dans des ateliers, par des spécialistes. Or, au XXe siècle, pour la première fois, cette conception de l’horlogerie comme artisanat est remise en cause, lorsque l’industrie japonaise présente un premier modèle de montre à quartz, fabriquée à la chaîne par des machines. L’alliance d’un mécanisme nouveau (donc séduisant) et d’un prix réduit permet au plus grand nombre d’accéder à l’objet-montre, et plonge la Suisse dans une terrible crise du quartz autour des années 70. Il faudra à la confédération helvétique adopter une stratégie marketing innovante pour s’extraire de ce piège et remonter doucement la pente.

Mais, depuis, le paysage a invariablement changé. Au troisième millénaire, l’histoire des montres se confond avec celle du progrès technologique : les mécanismes sont toujours plus petits et les montres toujours plus performantes. Aujourd’hui, le monde des garde-temps fait osciller ses aiguilles entre deux pans du même cadran : d’un côté, des objets qui cherchent à intégrer les technologies les plus récentes (comme les montres connectées) ; et de l’autre, des mécanismes encore produits à la main, avec le goût de l’artisanat, pour un public qui goûte le luxe et l’exception. Finalement, le monde n’est-il pas assez grand pour les contenir tous les deux ?

The history of watchmaking is that of a thousand-year-old conquest, which has seen the human race gradually take over the territories devolved to Time. From the invention of the first mechanisms of time flow to the development of the most advanced timepieces, the culmination of a world and millennium know-how, the history of watchmaking is a quest for Grail in which the essential is less the finality than the exploration of the mysteries of passing time.

The history of watchmaking: the first time

If it is indeed a secret that Man has perpetually sought to tame, it is that of Time. At the same time inconsistent and elusive, and yet terribly concrete for us humans who we see ineluctably grow old, Time has fascinated at least as much as the divine nature of the World. That’s why its history is at least as much the story of famous watchmakers as the amazing mechanisms they have delivered to humanity.

It is not surprising that we must go back to ancient Egypt, around the fifteenth century BC, to find trace of the very first sundial, an instrument of remarkable manufacture that allows indicate the flow of the day by following the celestial course of the day star, using a gnomon. The existence of such dials is then attested in several regions of the world, including Hellenistic Greece.

Once the man is infatuated with this strange project – mastering the intangible Time – he designs mechanisms that are more and more evolved. If the sundial sees its operation subject to the actual presence of the Sun, other instruments propose to measure durations without having to wait for the beautiful Apollon deign to leave its mark. This is the case of the clepsydra, or water clock, which offers to appreciate short durations with more than satisfactory precision. This is also the case of the fire clock, traces of use of which date back to the sixth century BCE, on the side of the Far East.

From clocks to watches

Remarkable though they are, these mechanisms are bound to be limited, some to the good will of the Sun, others to the sole measure of durations rather than the capture of an absolute Time. It was not until the fourteenth century that medieval Europe made a leap forward in the manufacture of timepieces, with the invention and then the installation of the first astronomical clocks, which at the same time aim at informing about service schedules. religious or public events, and to offer a mechanical vision of the solar system, obviously inspired by the model of Ptolemy.

Then follows a crucial period in the history of watchmaking, which sees French craftsmen, then Swiss, seek to develop existing systems and miniaturize them, until they are held on the tables of the aristocracy. The medieval clock soon becomes an object of prestige, as refined as practical, thought less to capture a portion of time than to decorate the interiors. This ambition of miniaturization will push up the making of the first models of complicated timepieces and pocket watches, models imagined to impress the royal courts and to confer renown on master watchmakers. It is here, in the hollow of medieval Europe, that the history of watchmaking becomes, strictly speaking, the history of watches.

From the Renaissance to the dawn of the modern world

The Renaissance period sees the culmination of this movement that turns clocks into watches. It was also at this time that the center of gravity of European watchmaking moved gradually towards Switzerland and England, oscillating from one nation to another, while France, thanks to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, sees fled a majority of its most brilliant watchmaking craftsmen. Geneva and London may be competing in timepieces, but together they have helped launch a history of modern watches, bringing these mechanisms into the era of precision.

But no doubt the history of watchmaking would not have been the same without the appetite of European courts for marine clocks. In the seventeenth century, the world is still young and needs to be discovered. Although the dangers of the oceans did not prevent great explorers from embarking, all navigators of the time agreed that the maritime movements would be much easier if they could calculate their longitude at any moment. Motivated by the promise of national recognition (and by the prospect of a royal bonus), the best minds of time set about designing a perfect marine clock. This is the first step in a race to mechanical precision that will not stop.

Like many sectors where invention is combined with commerce, that of watchmaking does not escape the wave of industrialization that affects the planet in the nineteenth century. With the mechanization of work, made possible by the development of machine tools and the division of tasks, Europe is entering a period of industrialization of watchmaking. Nineteenth-century watchmaking tends towards mechanization, and no one can escape it … Not even the Swiss craftsmen who take this route, not without having been pushed by the United States, where the industrial revolution of the watchmaking took root.

The history of watches since the 20th century

The appearance of the wristwatch determines the moment of entry into the watchmaking of the twentieth century. The pocket watch, a faithful jewel of the well-to-do classes, is gradually being replaced by models attached around the wrist, until the end of the First World War relegated the former to the state of antiquity. Now, the timepiece is worn as a bracelet and can be seen everywhere – in racing cars, in airplane cockpits, and up to the most extreme points on the globe, where watches faithfully accompany our bravest explorers.

By passing from the history of clocks to the history of watches, the human quest of Time has always kept its artisanal particularity: the design of mechanisms is done by hand, in workshops, by specialists. But in the twentieth century, for the first time, this concept of watchmaking as a craft is questioned, when the Japanese industry presents a first model of quartz watch, made to the chain by machines. The combination of a new (and therefore attractive) mechanism and a reduced price allows the greatest number to access the watch object, and plunges Switzerland into a terrible crisis of quartz around the 70s. to the Swiss confederation adopt an innovative marketing strategy to get out of this trap and slowly climb the slope.

But since then, the landscape has invariably changed. In the third millennium, the history of watches merges with that of technological progress: the mechanisms are always smaller and the watches always more powerful. Today, the world of timepieces oscillates its needles between two sections of the same dial: on the one hand, objects that seek to integrate the latest technologies (such as connected watches); and on the other hand, mechanisms still produced by hand, with the taste of craftsmanship, for an audience that tastes luxury and exception. Finally, is not the world big enough to hold both of them together?